Background: Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (UGIH) is a commonly seen complaint in the ED. Currently, endoscopy is the standard therapy shown to not only help with diagnosis, but also risk stratify patients and potentially offer effective hemostatic treatment of acute nonvariceal UGIH. What is frequently an area of debate, is the optimal timing of endoscopy. Even more frustrating is the different definitions of early endoscopy ranging anywhere from 1hr up to 24hrs after initial presentation.

Background: Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (UGIH) is a commonly seen complaint in the ED. Currently, endoscopy is the standard therapy shown to not only help with diagnosis, but also risk stratify patients and potentially offer effective hemostatic treatment of acute nonvariceal UGIH. What is frequently an area of debate, is the optimal timing of endoscopy. Even more frustrating is the different definitions of early endoscopy ranging anywhere from 1hr up to 24hrs after initial presentation.

Now on one hand, earlier timing of endoscopy could be associated with suboptimal resuscitation and potential hemodynamic instability. On the other hand, delayed endoscopy delays hemostasis from endoscopic therapy and increases the risk of rebleeding and need for surgery. I think we all agree that we should resuscitate our patients before endoscopy (or as I like to say resuscitate before you endoscopate), but is there a population of patients with UGIH that require sooner than later endoscopy? To talk about this topic we have a special guest Rory Spiegel. You can find Rory on twitter as @EMNerd_ or on the EMCrit blog where he discusses methodological issues with studies

Episode 36: Resuscitate Before You Endoscopate?

Click here for Direct Download of Podcast

Special Guest: Rory Spiegel

Twitter: @EMNerd_

Clinical Question: Is there a population of patients with Nonvariceal UGIH that require sooner (<6hrs) than later (>6hrs) endoscopy?

Time to Endoscopy Paper #1 [1]

What They Did:

- A systematic review of English language citations from 1980 – 2000

Outcomes:

- Tried to Answer 3 Questions:

- Does early endoscopy allow for safe and prompt discharge of low-risk patients with acute nonvariceal UGIH?

- Does early endoscopy improve patient outcomes vs delayed endoscopy in high risk patients with acute nonvariceal UGIH?

- Does early endoscopy reduce resource utilization vs delayed endoscopy for all comers with acute nonvariceal UGIH?

Inclusion:

- Studies including information regarding the effectiveness of early endoscopy determined by patient outcomes (mortality, rebleeding, transfusion requirements, need for emergency surgery, endoscopic complications, and readmission)

- Studies including economic outcomes (length of stay and direct costs)

Exclusion:

- Not written in English

- Non-human studies

- Not related to UGIH or lesions that can cause UGIH

- Solely related to variceal bleeding or other complications of portal hypertension

- Solely related to non-endoscopic interventions or complications

Results:

- 23 studies met inclusion criteria

- Does Early Endoscopy Allow for Safe and Prompt Discharge of Low-Risk Patients with Acute Nonvariceal UGIH?

- Only 3 Controlled Trials [2 – 4] evaluated early endoscopy vs “usual care”: All Trials with ≤110patients (Total Number of Patients = 213)

- Largest Trial (110 patients) [2] Compared Endoscopy <2hours vs “usual care” (24 – 48hours): 46% of patients with <2hour endoscopy avoided hospitalization and no complications or readmissions at 30days

- Does Early Endoscopy Improve Patient Outcomes vs Delayed Endoscopy for High-Risk Patients with Acute Nonvariceal UGIH?

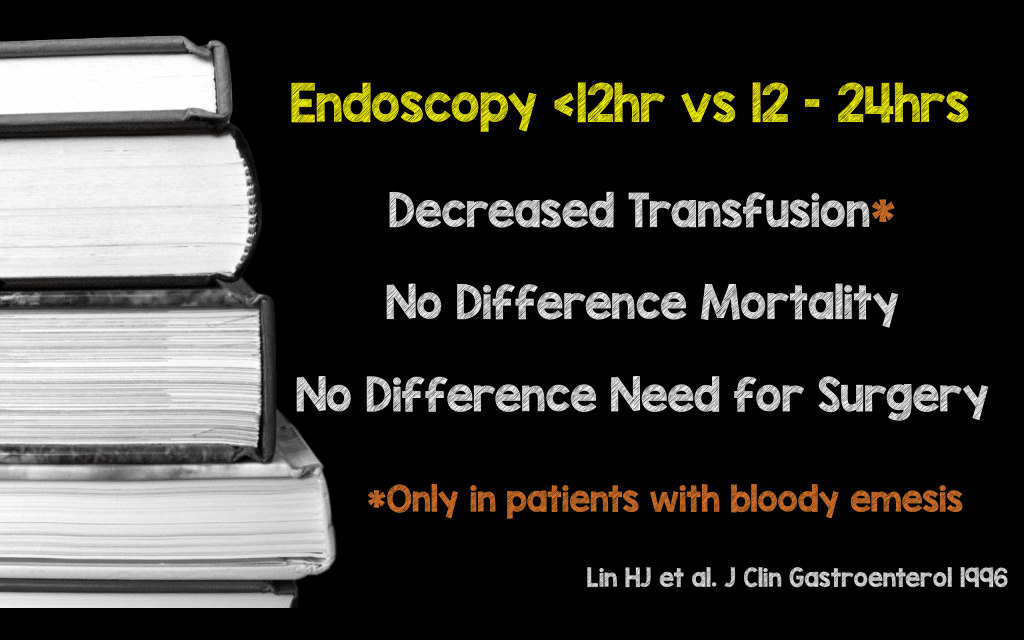

- Only 1 RCT [5] with 124 patients compared Early Endoscopy (<12hrs) vs Delayed Endoscopy (12 – 24hrs): Early endoscopy resulted in decreased transfusion requirement only for patients with bloody NGL aspirate but had no effect on mortality or need for surgery

- Does Early Endoscopy Improve Utilization Outcomes vs Delayed Endoscopy (1 – 2days) for All Comers with Acute Nonvariceal UGIH?

- Only 2 RCTs: One with low risk patients and the other with high risk patients

- Low Risk Patients [2]: 110 patients; Mean hospital stay decreased by 1 day and cost savings of $1594 per patient in the early endoscopy group compared to the delayed endoscopy group (1d vs 2d and $2068 vs $3662 respectively)

- High Risk Patients [5]: Early endoscopy saved 10.t days per patient compared with delayed endoscopy (4.0 +/- 3.5d vs 14.5d +/- 10.8d respectively) in patients with bloody aspirates but no effect on LOS in patients with coffee ground aspirates

- Only 2 RCTs: One with low risk patients and the other with high risk patients

Author Conclusion: “The overwhelming majority of existing data suggest that early endoscopy is safe and effective for all risk groups. The clinical and economic outcomes of early endoscopy should be confirmed in additional well-designed randomized controlled trials. Given the strength of evidence, efforts to develop a more standardized and time-sensitive approach to acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage should be undertaken.”

Time to Endoscopy Paper #2 [6]

What They Did:

- Nationwide cohort study based on a database of consecutive patients admitted to the hospital with PUB in Denmark

- Patients were stratified according to the presence of hemodynamic instability at presentation and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score

- Used descriptive statistics and logistic regression analyses to identify optimal time frames for endoscopy

Outcomes:

- Primary Outcome: In-hospital mortality

- Secondary Outcome: 30d mortality

Results:

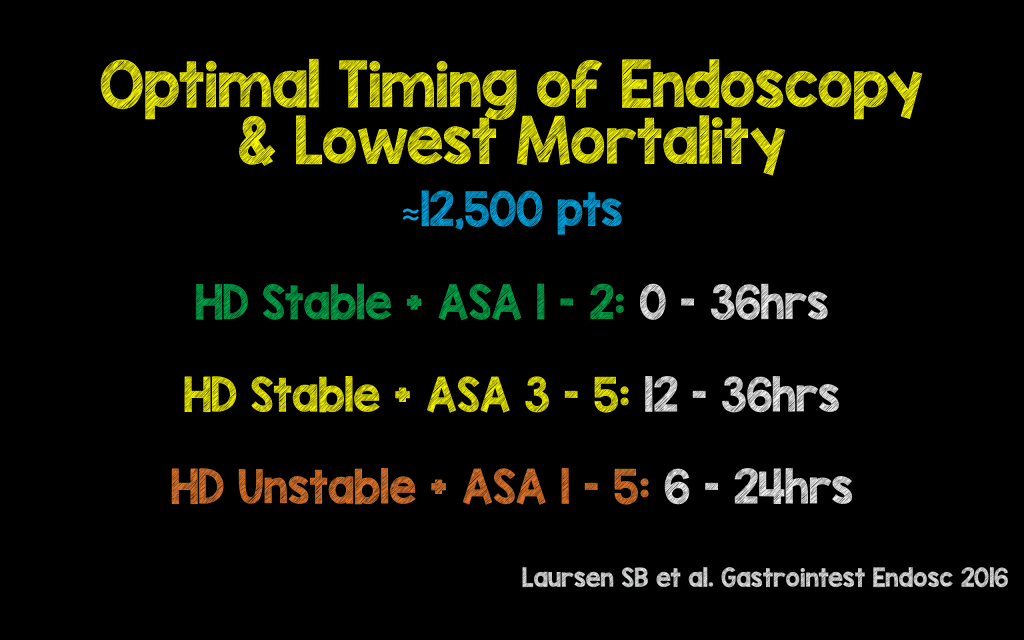

- >12,000 patients analyzed

- Stable Patients with ASA score of 1 – 2: No association between increased mortality and timing of endoscopy

- Stable Patients with ASA score 3 – 5: Endoscopy 12 – 36 hours after admission to the hospital was associated with lower in-hospital mortality (OR 0.48) compared to endoscopy outside this time frame

- Hemodynamic instability and ASA score of 1 – 5: Endoscopy at 6 – 24 hours after admission to hospital was associated with lower in-hospital mortality (OR 0.73) compared with endoscopy outside this time frame

Author Conclusion: “Timing of endoscopy is associated with mortality in patients with PUB and an ASA score of 3 – 5 or hemodynamic instability. Our findings suggest that in these patients, a period of time to optimize resuscitation and manage comorbidities before endoscopy may improve outcome.”

Issues Discussed with Rory:

- Patients Enrolled in Studies are Often Not Unstable: There is often a discrepancy between the patients we are thinking of when debating the timing of endoscopy and the patients these trials examine. In the first paper the patients deemed “high risk” were semi-stable patients. As a matter of fact, patients experiencing massive bleeds, variceal bleeds, or “could not participate in endoscopy” were excluded. It is difficult to consent unstable patients and therefore they are often not well represented or accounted for at all in research studies. The majority of patients evaluated in the first study are “low risk” patients (i.e. some sequelae of UGIH, not actively bleeding or hemodynamically stable). Only one RCT evaluated “high risk” patients defined as having a bloody aspirate on NG lavage.

- What is Meant by “Early” Endoscopy: There is a big discrepancy about what we mean by early endoscopy and what the literature defines as early endoscopy. In the first trial, early endoscopy is defined as within the first 24hours. What we often mean by early endoscopy is “get here as fast as you can.” It’s not surprising that these studies find very little difference between groups (i.e. <12hrs vs 12 – 24hrs).

- Sicker Patients Typically Get Earlier Endoscopy, But do Worse (i.e increased mortality) Because They are Just Sicker

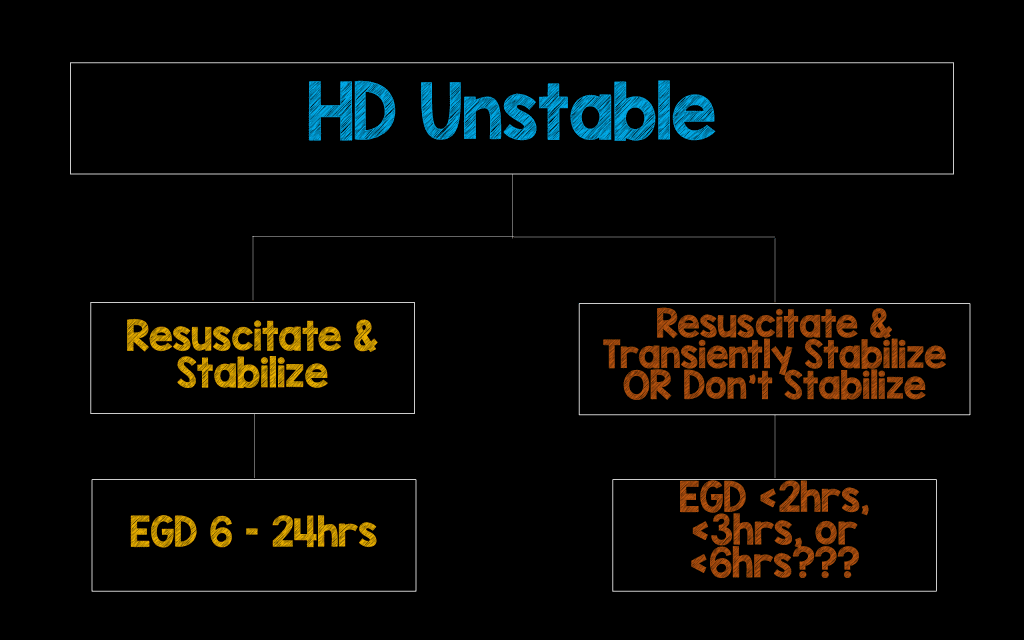

- Nonvariceal UGIH Can Be Divided into Sick and Not Sick: Another way to say this is hemodynamically stable and hemodynamically unstable. The sick patients should really be subdivided further sick and really sick. Those patients who respond to resuscitation and those who either transiently respond or don’t respond at all.

- Hemodynamically Stable: In patients without significant comorbid conditions and not actively bleeding one could argue scoping early (<6hrs) could afford early discharge and reduce costs but with no improvements in mortality. In patients with comorbid conditions or actively bleeding (i.e. melena, hematochezia) optimizing chronic and acute medical conditions is probably warranted with a delayed endoscopy (12 – 24hrs). The bottom line here is the timing of endoscopy for these patients is probably dependent on the time they arrive to the emergency department.

- Hemodynamically Unstable: First and foremost, these patients should get adequate resuscitation. Some patients will be responders and some patients will be transient responders or won’t stabilize at all. The patients that stabilize will most likely be admitted to the ICU and should probably get an endoscopy sooner than later, but one could argue 12 – 24 hours would be acceptable. There is a lot of grey area here where some patients who do stabilize for whatever reason may need endoscopy sooner than the next day. For the patients that transiently stabilize or don’t stabilize at all despite maximal medical therapy, what is the optimal time for endoscopy: <6hrs, <3hrs, or maybe <2hrs? There is very scant evidence evaluating this population. Our GI colleagues will say there is a high mortality associated with doing endoscopy in these patients early, but then again, these patients probably have a higher mortality despite the endoscopy itself. There is no real clinical evidence or physiological reason why sick patients will become more unstable during endoscopy. If they already survived the hemodynamic turmoil of intubation then endoscopy shouldn’t add any further serious stress to their compromised system. In the sickest of the sick, there really should be no time period of optimal endoscopy other than “as soon as GI can get there.”

Clinical Take Home Point:

In HD unstable patients the triage point to deciding on how early to perform endoscopy is response to resuscitation. If they stabilize, they can go to the ICU with frequent assessments with a courtesy call to our GI colleagues. The patients who transiently stabilize or don’t stabilize at all despite resuscitation (i.e. Already doing everything that we can from a medical standpoint: blood products, pressors, intubation, PPI, Octreotide, etc.) need hemostasis and the only way this is going to happen is with endoscopy. For these patients, we need to get GI in at whatever time of the day it is. So you still resuscitate before endoscopy (or as I like to say resuscitate before you endoscopate), but the response to that resuscitation is what determines who should get scoped sooner (i.e <2hrs, <3hrs, <6hr etc…)

References:

- Spiegel BMR et al. Endoscopy for Acute Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Hemorrhage: Is Sooner Better? Arch Intern Med 2001. 161 (11): 1393 – 404. PMID: 11386888

- Lee JG et al. Endoscopy-Based Triage Significantly Reduces Hospitalization Rates and Costs of Treating Upper GI Bleeding: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastrointest Endosc 1999. 50(6): 755 – 61. PMID: 10570332

- Campo et al. Safety of Out-Patient Management of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Preliminary Results of a Randomized Study [Abstract] Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 47: AB81. Abstract 228

- Brullet et al. Outpatient vs. Hospital Care After Endoscopic Injection in Selected patients leeding From Peptic Ulcers: Preliminary Results of a Randomized study [Abstract] Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 47: AB81. Abstract 227

- Lin HJ et al. Early or Delayed Endoscopy for Patients with Peptic Ulcer Bleeding. A Prospective Randomized Study. J Clin Gastroenterol 1996. 22(4): 267 – 71. PMID: 8771420

- Laursen SB et al. Relationship Between Timing of Endoscopy and Mortality in Patients with Peptic Ulcer Bleeding: A nationwide Cohort Study. Gastrointest Endosc 2016. S0016-5107(16):30555-7. PMID: 27623102