Background: Hyperkalemia is the most common electrolyte disorder seen in the Emergency Department and treatment of hyperkalemia is core knowledge of EM training for interns and focuses on:

Background: Hyperkalemia is the most common electrolyte disorder seen in the Emergency Department and treatment of hyperkalemia is core knowledge of EM training for interns and focuses on:

1) Stabilization of cardiac myocytes with calcium salts2) Temporary shifting of potassium into cells (insulin, beta agonists, normal saline,magnesium, sodium bicarbonate)3) Removal of potassium from the body (i.e. loop diuretics, cathartics)4) Definitive Treatment (i.e. Hemodyalisis)

Although there is still some debate on the first two areas (i.e. is there truly a role for sodium bicarbonate?) our focus will be on the removal part of the algorithm, specifically, is there a role for kayexalate?

Kayexalate (Sodium polystyerene sulfonate) is a cation-exchange resin that was approved in 1958 as a treatment for hyperkalemia by helping to exchange sodium for potassium in the colon and thus excreting potassium from the body. This drug has been a standard part of treatment of hyperkalemia for decades. Many of us were taught that if you give a patient a dose of kayexalate, you should expect there serum potassium to drop by 0.5 – 1.0 mEq in 4-6 hours.

Kayexalate (Sodium polystyerene sulfonate) is a cation-exchange resin that was approved in 1958 as a treatment for hyperkalemia by helping to exchange sodium for potassium in the colon and thus excreting potassium from the body. This drug has been a standard part of treatment of hyperkalemia for decades. Many of us were taught that if you give a patient a dose of kayexalate, you should expect there serum potassium to drop by 0.5 – 1.0 mEq in 4-6 hours.

The evidence for this recommendation comes from 2 articles in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1961. The first thing that becomes obvious when reading these studies is that what was considered strong evidence 50 years ago wouldn’t be accepted today in any major journal.

Flinn RB et al. Treatment of the oliguric patient with a new sodium-exchange resin and sorbitol; a preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:111. PMID: 13700297

Population: 10 patients with severe oliguriaIntervention: Sorbitol + a cation exchange resin (+ a no potassium diet)Control: Sorbitol alone (+ a no potassium diet)Outcome: Decreased potassium level at 5 days

Findings: All patients in both groups had decreased serum potassium levels at 5 days. There is no statistical analysis performed to tell us that one treatment is better than another but it doesn’t appear that way. In spite of this, the authors argue for the use of the cation exchange resin.

Scherr L et al. Management of hyperkalemia with a cation-exchange resin. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:115. PMID: 13747532

Population: 32 patients with acute or chronic renal failure.Intervention: Oral (or rectal) cation exchange resin and a low or no potassium dietControl: NoneOutcome: Serum potassium 24 hours post-administration

Findings: Scherr and colleagues found a decrease in serum potassium by 1.0 mEq on average.

Gruy-Kapral C et al. Effect of single dose resin-cathartic therapy on serum potassium concentration in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Nephrol 1998; 9(10): 1924-30. PMID: 9779734

Population: 6 patients with renal failureIntervention: Single dose of a cation exchange resin + sorbitolControl: NoneOutcome: Serum potassium level at 12 hours

Findings: The authors found no difference in serum potassium levels at 12 hours.

Commentary: The Flinn and Scherr studies both conclude that the use of cation exchange resin + sorbitol is beneficial in the treatment of hyperkalemia. However, the results of their studies do not defend this conclusion. In the Flinn study, they were looking primarily at outcomes 120 hours after administration. Hardly the endpoint that we care about in the Emergency Department (I would argue that even the inpatient people wouldn’t care about this endpoint). In the Scherr study, there was no control group and the decrease was seen at 24 hours, again, not what we would care about in the ED. Both of these studies lacked even a modicum of randomization and all patients were given low/no potassium diets.

Commentary: The Flinn and Scherr studies both conclude that the use of cation exchange resin + sorbitol is beneficial in the treatment of hyperkalemia. However, the results of their studies do not defend this conclusion. In the Flinn study, they were looking primarily at outcomes 120 hours after administration. Hardly the endpoint that we care about in the Emergency Department (I would argue that even the inpatient people wouldn’t care about this endpoint). In the Scherr study, there was no control group and the decrease was seen at 24 hours, again, not what we would care about in the ED. Both of these studies lacked even a modicum of randomization and all patients were given low/no potassium diets.

These two studies from the NEJM are the basis upon which kayexlate has been prescribed for 5 decades but they prove nothing except that patients given minimal dietary potassium their serum level will fall over 24 hours.

Finally, we have a Cochrane Review (Mahoney 2005) that states that potassium-absorbing resins have never been found to be effective in the first hours of treatment.

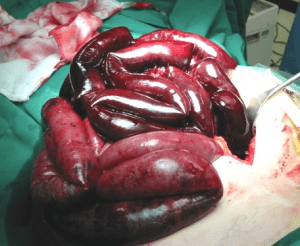

Alright, so a review of the literature shows that there is virtually no benefit in the emergent setting to the use of kayexalate. But is there a downside? As with all medications, there is. In this case, there is a rare but highly lethal complication of the drug: Colonic Necrosis.

A number of case reports and case series (Lillemoe 1987, Gerstman 1992, Rogers 2001, Bomback 2009) detail patients with kayexalate-associated colonic necrosis. In fact, the FDA added a warning back in 2011 cautioning against the use of the drug for this reason.

Given th e absence of any significant benefit, particularly in the emergent setting, and the potential for serious harm, this recommendation from the nephrology literature seems very reasonable:

e absence of any significant benefit, particularly in the emergent setting, and the potential for serious harm, this recommendation from the nephrology literature seems very reasonable:

“It would be wise to exhaust other alternatives for managing hyperkalemia before turning to these largely unproven and potentially harmful therapies.” (Sterns 2010)

So there you have it. More dogma-lysis on a medical myth that has been passed down from generation and purported for 50 years.

Okay, so what should I do with the hyperkalemic patient?

- If they have EKG changes, give Ca2+ salts and standard temporizing therapy and get the patient dialyzed if necessary.

- If you have to wait for dialysis, continue to redose your temporizing meds

- Look for the underlying cause – missed dialysis? ACEI? NSAIDs? Etc.

References:

- Flinn RB et al. Treatment of the oliguric patient with a new sodium-exchange resin and sorbitol; a preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:111. PMID: 13700297

- Scherr L et al. Management of hyperkalemia with a cation-exchange resin. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:115. PMID: 13747532

- Gruy-Kapral C et al. Effect of single dose resin-cathartic therapy on serum potassium concentration in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Nephrol 1998; 9(10): 1924-30. PMID: 9779734

- Mahoney BA et al. Emergency interventions for hyperkalemia (Review). Coch Data Syst Rev 2005 Issue 2. CD 003235

- Lillemoe KD et al. Intestinal necrosis due to sodium polystyrene (Kayexalate) in sorbitol enemas: clinical and experimental support for the hypothesis. Surgery 1987; 101(3): 267-72. PMID: 3824154

- Gerstman B et al. Intestinal necrosis associated with postoperative orally administered sodium polystyrene sulfonate in sorbitol. Am J Kidney Dis 1992;20(2):159-61. PMID: 1496969

- Rogers FB, Li SC. Acute colonic necrosis associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) enemas in a critically ill patient: case report and review of the literature. J Trauma 2001; 51(2): 395-7. PMID: 11493807

- Bomback AS et al. Colonic necrosis due to sodium polystyrene sulfate (Kayexalate). Am J Emerg Med 2009; 27: 753.e1-e2. PMID: 19751641

- Sterns RH et al. Ion-Exchange Resins for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia: Are They Safe and Effective? J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21: 733-5. PMID: 20167700